Although their ordeals occurred at different times and under separate arrangements, the harrowing similarity of their experiences highlights a growing crisis of human trafficking targeting vulnerable East Africans.

Philip Ruto, a soft-spoken young man in his 20s from Mt Elgon, had just completed his training as a plant mechanic through the National Youth Service in April last year.

He had high hopes of using his skills to change his family’s life. But when months went by with no job in sight, desperation set in.

“I was getting tired of sitting at home. Then a family contact told me about a job in Thailand,” he said.

“They said it was a tech company that needed people with basic computer skills. It sounded legit.”

Ruto wasted no time. He applied for a passport for Sh7,500 and, through a connection in Nairobi, obtained a visitor’s visa to Thailand.

The entire trip, including logistics, cost more than Sh75,000, money his father borrowed from neighbours and relatives.

“I didn’t want to disappoint my family. We thought it was an investment,” Ruto said

He flew out of Nairobi on December 31 last year. At the airport in Bangkok, he was greeted by a stranger who identified him using a photo sent via Telegram.

All communication with the agents was conducted through Telegram, an encrypted platform favoured by traffickers, making their operations nearly invisible.

He never passed through official immigration. Instead, he and two other Kenyans who had also traveled independently were bundled into a vehicle and driven for seven hours through remote parts of Thailand.

“By the time we got to the river, it was already dark,” Ruto recalled.

“Then they put us in a boat. I remember crossing quietly and thinking, ‘This doesn’t feel like a job trip anymore.’”

STARVED AND TORTURED

On the other side, armed men were waiting. The group was taken into the forest and delivered to what appeared to be a scam compound. There was no office, no company, no contracts.

“They told us we were now online scammers. They trained us on how to use fake names and trick people online,” Ruto said.

“I had to chat with people, pretending to be someone I wasn’t. I felt trapped.”

Each worker was given eight smartphones, each connected to multiple fake identities targeting foreign victims. Mistakes were met with brutal punishments.

“If you were late replying to a client or made an error, you could be beaten or locked in a dark room,” he said.

“I saw people tortured. One guy was forced to kneel on bottle caps for hours.”

Sleep was rare. The working hours stretched from 9pm to 8am. Their beds were rough wooden boards. Food was minimal.

“At some point, I just stopped feeling hungry. The stress was too much. I just wanted to survive.”

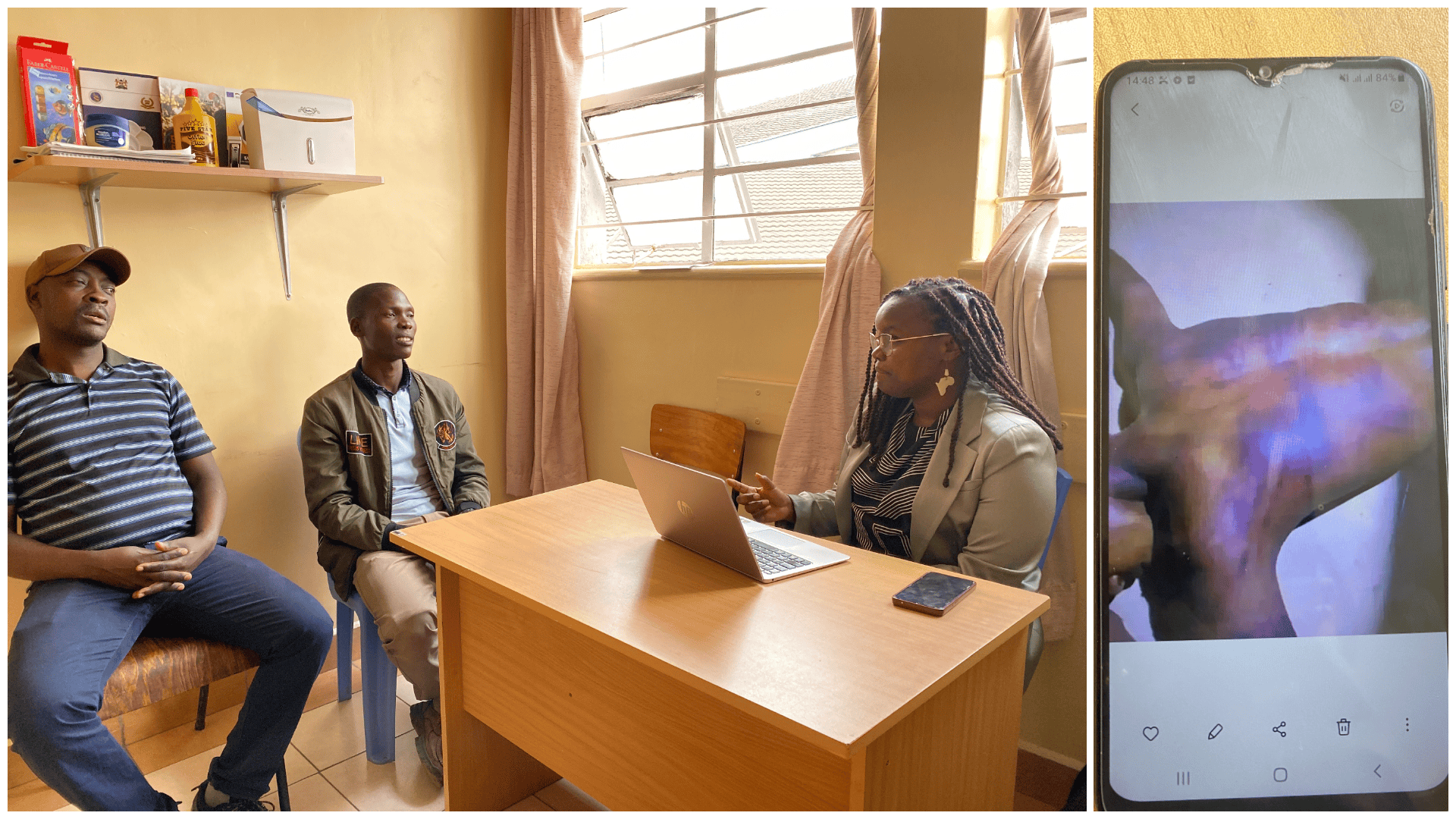

Salvation came when one of the Kenyan victims managed to secretly record scenes of abuse and escaped. The footage reached the authorities, triggering diplomatic efforts that led to a rescue mission. Ruto was among those repatriated back to Kenya earlier this year, where he was received by officials from Awareness Against Human Trafficking (HAART) Kenya.

“When I landed back home and saw the HAART Kenya officials, I broke down,” he said. “They gave us food, clothes and told us we were safe. That’s when I realised I was really free.”

ANOTHER VICTIM

Weeks later, in a completely separate case, Dennis Mosoti from Kisii county would fall into the same trap.

Mosoti, who had lived in Nairobi’s Embakasi area, had spent years trying to make a living, working in Githurai, selling eggs in Tassia, and picking up casual jobs. But nothing stuck.

“I told my friend that even if I have to borrow money, I just want to go abroad. I’ll do anything,’” he said.

That conversation led to an introduction to a woman who claimed to have job connections in Thailand.

Desperate, Mosoti’s mother withdrew her NSSF savings to raise Sh100,000 for his travel. Like Philip, all arrangements from flights to visa applications were done over Telegram.

“I didn’t even know the woman’s real name. Everything was just messages and voice notes,” Mosoti said.

He flew out in February, weeks after Philip had returned home. When he landed in Bangkok, he was picked up and driven for hours with a group of other Kenyans. As night fell, they, too, were ferried across the border by boat.

“When I saw men in military gear holding rifles, my heart sank,” Mosoti said.

“That’s when I knew I wasn’t in Thailand anymore.”

Inside the guarded compound in Myanmar, his phone and passport were confiscated. The syndicate handed him a fake American identity: Bob Timberly.

“They gave me a fake ID card and trained me to pretend I was a rich investor,” Mosoti said.

“I had to chat with real estate agents in the US, act interested in buying property, then slowly introduce them to fake crypto investments.”

He said meals were rationed. Surveillance was constant.

“If you asked too many questions or tried to contact someone outside, they threatened to sell you to another group for organ harvesting or hand you to the army,” he said.

After six agonising weeks, some members of the group began to resist. Word of their situation leaked out to Thai officials, and diplomatic pressure began to mount. The traffickers eventually relented, returning their passports, erasing their phones and releasing them under watch.

“I went looking for work. I came back with trauma,” Mosoti said.

“I can’t forget what I saw there.”

SPEAKING OUT

Today, both men are speaking out to warn others.

“This thing is real. If someone offers you a job abroad on Telegram and it sounds too easy, run,” Ruto cautioned

“We just wanted better lives. But not every opportunity is worth the risk. Sometimes, it’s a trap dressed as a dream.” Mosoti said.

The Kenyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs has since issued warnings against travelling to Southeast Asia without verified job contracts. But for men like Ruto and Mosoti, the scars run deeper than policy.

In a statement issued on June 27, Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs voiced deep concern over the escalating threat posed by transnational crime syndicates operating scam call centres, engaging in online fraud and trafficking vulnerable individuals across Southeast Asia.

“These crimes have caused immense economic and social damage to people around the world,” the ministry said, referencing recent reports by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime and Amnesty International that highlighted the regional scope of exploitation.

The Thai government stressed the urgency of cross-border cooperation, pledging to take “a leading role in coordinating international efforts to combat transnational crime”.

The statement emphasised that the Thai government would engage “only through official diplomatic channels” when addressing sensitive bilateral concerns, an apparent response to increasing public discourse on the trafficking crisis in neighbouring countries.

“The Royal Thai Government urges the international community to collaborate closely with Thailand in suppressing these crimes, which pose a direct threat to the security and well-being of people in the region.”

SURVIVORS’ LIFELINE

When survivors of human trafficking return home, bruised, traumatised and burdened with debt, it’s often HAART Kenya waiting for them at the airport.

The organisation, which started in 2010, has become a national lifeline for victims and families confronting one of the most complex and fast-evolving crimes of our time.

HAART Kenya advocacy manager Winnie Muteru sits at the heart of this response.

She breaks down the grim mechanics of the industry — the false job offers, forged documents, deception and the thin, often invisible line between opportunity and exploitation.

“Our work started in Kenya but now spans the region, because trafficking doesn’t stop at borders and neither can we,” she said.

HAART’s programming is structured around what Muteru calls “the four Ps”: Prevention, Protection, Prosecution and Policy.

In prevention, the organisation runs training sessions in schools, churches and communities, targeting young people and first responders.

“We believe in going to the people before the traffickers do,” Muteru said.

Their helpline allows the public to report suspected trafficking cases. But that’s just the beginning.

“We also provide protection. We have a shelter for trafficked women and girls, and outreach programmes for survivors who return to their communities. The trauma is deep, but recovery is possible,” she said.

Prosecution is another pillar. HAART supports survivors through legal processes, a daunting path given the challenges in Kenya’s justice system.

The Kenyan law prescribes a minimum of 30 years in prison or a Sh30 million fine for trafficking. But in reality, sentences are often lower and restitution for survivors is rare. And there are other gaps.

“A victim rescued from a brothel might be classified as a sex worker,” Muteru said.

“A child forced to work may be treated as just another case of child labour. But these are trafficking crimes and they [should] carry heavier penalties.”

Earlier this year, HAART Kenya helped facilitate the rescue and repatriation of more than 150 Kenyans trafficked to scam compounds in Myanmar.

“This wasn’t just about forced labour. These were skilled professionals, university graduates tricked with promises of jobs in Thailand’s tech industry,” she said.

“Once there, they were smuggled across borders into guarded compounds run by rebel groups.”

Inside, the horrors unfolded, forced online scamming, electric shocks, starvation, even organ harvesting.

“You’re trained on how to scam people,” she noted

“You have daily financial targets. If you fail, you’re beaten. If you’re no longer useful, you’re disposed of. It’s modern slavery wearing a digital mask.”

She noted that some were so badly injured that they returned to Kenya with permanent deformities. Others arrived home empty-handed, still saddled with travel loans they took to chase what they thought were real job opportunities.

She cautioned that what’s perhaps most chilling is how organised traffickers are and how broken the systems meant to stop them remain.

“These criminals are exploiting the very loopholes we’ve created. You’re told to travel on a tourist visa. You’re coached on what to say at the embassy. Sometimes, you’re even handed a bribe to use at checkpoints,” Muteru said

She indicated that more disturbing is how traffickers are often people the victims know.

“Most of the people we spoke to were trafficked by friends, family or someone who had helped them travel before,” Muteru said.

“It’s betrayal wrapped in trust.”

CHANGING THE NARRATIVE

From September last year, HAART began coordinating closely with Kenya’s embassy in Thailand after receiving distress calls from families and survivors.

By early this year, with support from the Thai government, international media and even China’s diplomatic corps, dozens were rescued.

“Electricity and Internet were cut off at the compounds, and that forced traffickers to release people. The rebel groups didn’t want global backlash,” Muteru recalled.

She noted that In Kenya, HAART led multi-agency coordination with the Directorate of Criminal Investigations, Kenya Airways and diaspora affairs officials to safely receive survivors, conduct medical screenings and reunite them with their families.

But Muteru warns that the trafficking threat is far from over.

“We’ve got reports of Kenyan victims now in Cambodia, Vietnam, the same scam operations, and different countries. This isn’t just an African issue anymore. It’s global.”

Muteru warned that awareness alone isn’t enough and that prevention must begin long before the airport.

“There are red flags,” she says. “If you’re being coached to lie at the embassy, if your job offer lacks legal documents, if your visa is a tourist one and you’re told work permits will come ‘later’, stop. These are traps.”

She adds, “We’ve had victims come back in coffins. Others came back with diseases, trauma, debt. And still, they consider leaving again because the root problem is poverty and lack of opportunity.”

HAART Kenya is now pushing for broader systemic reforms, such as easier access to legal migration processes, stronger regional coordination and survivor compensation.

“We cannot keep exporting our young people and calling it development. We need jobs here. And we need the government to fix the broken systems traffickers are exploiting,” Muteru said.

In a statement on February 18, the Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs reiterated its warning to Kenyans against falling prey to deceptive job offers.

“Traffickers are using Thailand as a trapdoor to lure vulnerable youth into Myanmar,” the ministry cautioned.

It further urged those seeking employment abroad to consult official channels before travelling.

“Kenyans interested in jobs advertised in Thailand should get in touch with the ministry or the Kenyan Embassy in Bangkok to authenticate any such offers before traveling abroad.”