I loved doing the reviews and often marvelled at the fact that I was getting paid to enjoy the pursuit of my favourite things.

The only thing I objected to in my job as a reviewer was the ever-present shadow of the Film Censorship Board. The government made liberal use of it to curtail free speech and prevent any ideas of dissent through plays and films.

I had grown up in a time when the government of the day thought nothing of banning a stage play and jailing its writers.

For instance, in 1977, the Kenya government banned the play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), co-written by Ngugi wa Thiong'o and Ngugi wa Mirii, and detained Wa Thiong’o without trial for good measure.

I was an impressionable boy when that happened, and Wa Thiong’o was a family friend.

In 1982, a restaging of Joe de Graft’s Muntu was banned despite the fact that it was an 'O' level set book and had been performed several times. This rendition by the Kenyatta University College, which was being staged as an aide for examination candidates, was banned by the Ministry of Higher Education for allegedly being “too violent”.

In February 1991, as the clamour for the return to a multiparty democracy in Kenya grew, the government banned the play Shamba la Wanyama, based on George Orwell’s Animal Farm. My generation had studied it as a set book in school.

Other plays banned by the state censor in those troubled times include Oby Obyerodhyambo’s Drumbeats on Kirinyaga, a provocative African folk tale criticising greed, and Egyptian writer Tewfik al-Hakim's The Fate of a Cockroach, written in 1966.

Though the play satirises the regime of President Gamal Abdel Nasser as well as the feminist uprising in Egypt during the 1960s, in 1990s Kenya, the censor wanted to know whether the cockroach was referring to President Moi.

The censor’s red pen did not disappear with the promulgation of the 2010 constitution. We all remember the over enthusiastic Ezekiel Mutua and his shenanigans. He once even tried to censor an encounter in nature where two male lions had sex.

In 2025, Kenya has a government that outwardly likes to boast about its “digital transformation agenda”, which it claims is “aimed at leveraging technology for economic growth and job creation”, but that deep down inside wants to revert to analogue times.

The state seems to have no idea how the digital world works and would rather turn back the clock to the 1980s and before, to a time when it could control most of the information that made it to the public.

Look at the recent fuss over Echoes of War, the controversial Butere Girls’ entry to schools’ drama festival.

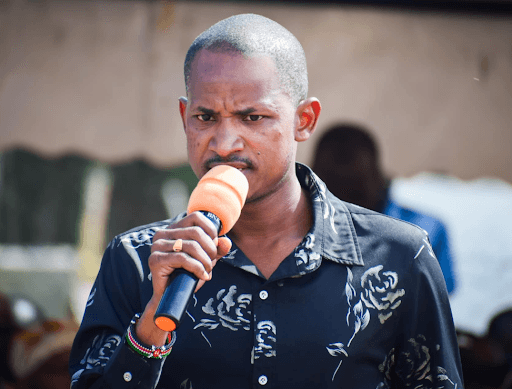

The state appears to have shot itself in the foot to stop the staging of the play, whose writer, Cleophas Malala, was until very recently deeply embedded into the fabric of Kenya Kwanza as the party’s secretary general.

When the first action was taken against the play a few weeks ago, it was all over social media from WhatsApp, Telegram, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, BlueSky and TikTok in seconds.

Shortly afterwards, the matter went to court and the court allowed the play to go on. The government was still champing at the bit and arrested its writer, Malala, just as the play, which was now nationally famous, was about to be staged.

This caused the students to walk out of the competition, and if the government thought it was all over bar the shouting, it was wrong.

Within minutes of the walkout, the play’s script was doing the rounds on WhatsApp. Elsewhere and by the end of the week, as Education CS Julius Ogamba played semantic games with reporters, the Standard newspaper ran the whole script in its Saturday edition.

Digital technology had analogue censorship for lunch and showed that “it’s impossible to stop an ejaculation once it has left the testicles”, as someone said rather crudely on social media. But you get the point, even through the government seemingly doesn’t.