As for medicine, the institutions still referred to as “mission hospitals” were often the only such institutions for many miles, in places where the colonial authorities did not feel it necessary to provide medical services.

And in any case, the only qualified personnel for running such hospitals were bound to be doctors who were affiliated with one of the missionary organisations, who felt a “calling” to go out into the “wilderness” and serve the people who lived there.

But above all, there is commercial agriculture. I specify “commercial” to distinguish it from the kind of subsistence agriculture that existed more or less in every human community around the world that had progressed beyond the hunter-gatherer level of existence.

Such commercial agriculture, which involves the creation of large surpluses of agricultural commodities that are grown in one place and sold in some other place, often very far away, has been the foundation of modern life across the world, and even the basis for urbanisation and the acquisition of specialised skills.

In any place where everyone grows their own food, agriculture tends to be a fulltime occupation, leaving very little time for anything else. But once agriculture is commercialised and adequate surpluses of grains and vegetables may be expected, a community then becomes “food secure”, as we say these days. And this in turn allows for various other occupations and specialisations to be undertaken by those who are now confident that they will be able to offer their own goods and services in exchange for food.

And commercial agriculture also requires modern infrastructure: roads, railways, water supply systems and so on.

So once the decision was made to bring “white settlers” to take up vast tracts of land in Kenya and convert what was mostly savannah grasslands into modern large-scale farms and ranches, a process was launched that ultimately entrenched commercial farming in Kenya.

Initially, all the truly valuable cash

crops were listed as “scheduled crops”, which could only be grown with the

permission of the colonial administration, and which indigenous Kenyans were

quite specifically denied any opportunity to grow. But in the end, it was this

development that guaranteed that when at last Independence was attained in

Kenya, what the Jomo Kenyatta government took over was a nation built on a firm

foundation of commercial agriculture.

WHAT IF…?

To this day, agriculture remains the backbone of the Kenyan economy, and the single biggest employer of labour in the country. About 40 per cent of the Kenyan workforce is employed in agriculture, in contrast with about 1.6 per cent of the American workforce and 2.5 per cent of the French workforce.

The idea that the modern state we call Kenya would not have been possible if we had never been colonised, is one which is not likely to be welcome to most indigenous Kenyans.

The preferred narrative tends to focus on the fact that our various ancestral lands were occupied by a foreign invading force. Our ancestors were then dispossessed and oppressed, and in time, we rose to defy the foreigners, and we fought for, and won, our freedom.

But the question remains: if the settlers had not been offered the prospect of a life that they could not possibly have had the opportunity or resources which would have enabled them to live in such a manner in their own country, would they have come at all?

And if they had not come and built that foundation of commercial agriculture on which the Kenyan economy depends to this day, would we have inherited a modern state that had agricultural goods to sell to the rest of the world?

Would we have ever been a top exporter of coffee or tea, and more recently, horticultural crops?

And then, of course there is tourism, the other key pillar of the Kenyan economy, which is very much an inheritance from Kenya’s colonial past.

As Jake Grieves-Cook, a veteran of Kenya’s tourism industry and wildlife conservation fraternity, explained in response to my inquiry via email:

“[The] foundation of the tourism sector in Kenya, which flourished in the years after Independence, was laid in in the colonial period.

One of the key figures in establishing national parks and game reserves in Kenya was Mervyn Cowie, a name that many will not be familiar with today, but who deserves credit as being the person whose endeavours resulted in national parks being established in Kenya in 1946, even before the first one was set up in Britain.

Cowie was born in Nairobi in 1909, the son of early British settlers. After university in Britain, he returned home to Kenya and became convinced that unless wildlife parks were set up, the animals would be exterminated to make way for agriculture or would be wiped out by hunting, and that this would be a huge loss of a natural resource.

He had to overcome the initial opposition of the colonial authorities, and it was his efforts that resulted in Nairobi National Park being established in 1946, followed by the other parks and reserves.”

PROGRESS WITHOUT COLONISATION?

The difficult point we have to consider is this:

First, we have to concede that it is a good thing that when the moment came for Kenya to gain its Independence, there was in place a strong foundation laid for an initial (and widely shared) rural prosperity based on a viable cash crop economy.

And subsequently, the expansion of the tourism sector, which was to include the establishment of the first hotel school in East Africa a decade and a half after Independence, ranks as a plus.

This, then, raises the question: If it were not through being colonised, how else could the foundation for economic opportunity have been built in the rural parts of Kenya, where most of our people live? Or the many beach hotels and safari lodges and tented camps been built in national parks, whose boundaries were demarcated back in the colonial era?

Would these benefits really have come if not through people who came here in pursuit of their own (often delusional) dreams and aspirations? People who were part of the colonial system of government, which had little respect for what we would now recognise as the property rights and human rights of the indigenous communities?

SHORT-SIGHTED MEMOIR

As for the personal memoir, I think this is a case of a writer over-dramatising the experiences of his childhood in a (by now) remote and exotic land.

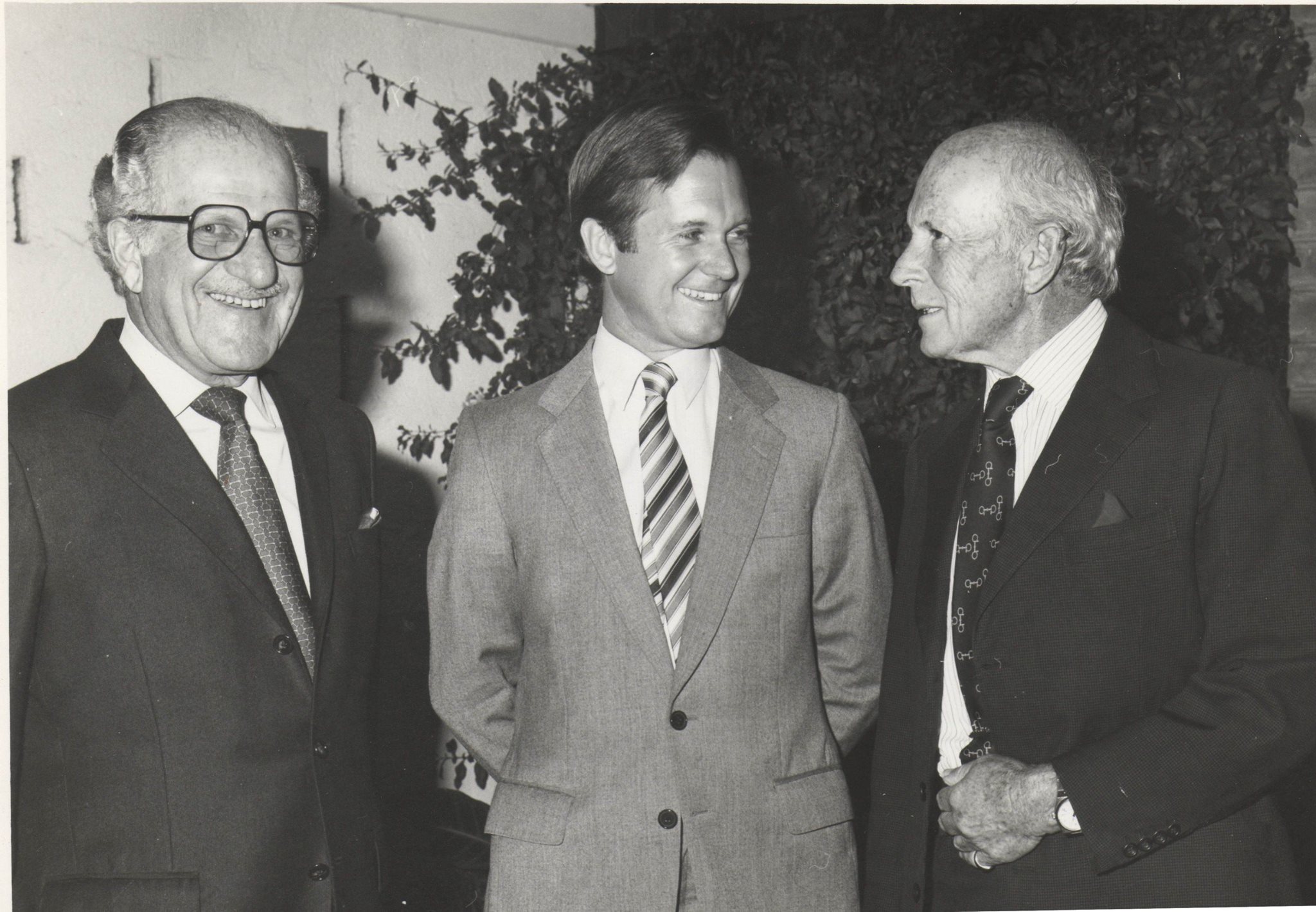

The aforementioned Jake Grieves-Cook is an example of those who chose to remain in Kenya after Independence and managed to make significant contributions to what we in Kenya call “nation building”, even as they successfully pursued their own individual aspirations and plans.

Grieves-Cook, whose father was a teacher and then Provincial Inspector of Schools with the Ministry of Education, is a Kenyan citizen who grew up in Kenya in the 1960s and then went to the UK to complete his education at Oxford. Thereafter, he returned to Kenya in 1972 to start his tourism career spanning nearly 50 years.

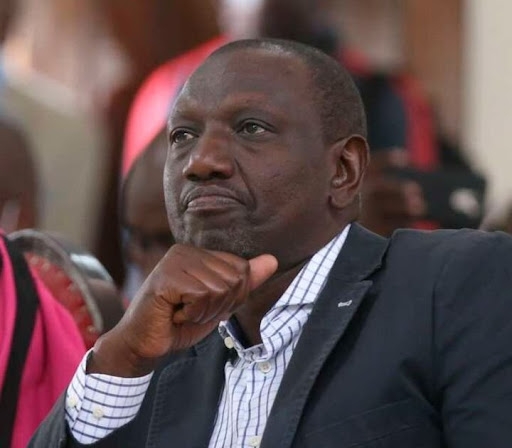

Kenya, for all its many failings as a

nation, is a country notable for its interracial tolerance. This emphasis on

mutual forgiveness and tolerance was a key plank of the message of

reconciliation preached by our founding President, Jomo Kenyatta. And by now it

is widely regarded as something that the old man (Kenyatta was an estimated 75

years old when he became President) got right.

And as such, we Kenyans may be

forgiven for being a little impatient with those who did not stay here very

long, and yet now declare themselves to be “trapped in history”.