Civil society organisations have joined growing calls for the abolishment of the Kafala system in the Gulf countries where Kenyan migrant workers have fallen victim.

Amnesty International and Trace Kenya said the system fosters exploitation of migrant workers and promotes racism.

“We are calling for the unequivocal dismantling of the Kafala Sponsorship System that binds foreign workers to employers, that fosters exploitation and perpetuates racism,” Amnesty International Kenya executive director Houghton Irungu said Tuesday.

Trace Kenya director Paul Adoch said the Kafala system has caused untold suffering for Kenyan migrant workers, especially those from the Coast region.

Adhoch noted that, disproportionately, the Coast region has the largest number of women travelling to the Middle East.

The Kafala system, also known as sponsorship system, defines the relationship between foreign workers and their local sponsor, known as kafeel, usually their employer.

The system gives private citizens and companies in the Gulf countries almost total control over migrant workers’ employment and immigration status.

It arose from growing demand in Gulf economies for cheap labour, and desperation of many migrants in search of work.

Under the system, employers have been reported to confiscate the passports and phones of migrant workers, as a way of controlling them.

Calls for the reforms have been growing since the preparations for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar drew international scrutiny to the system and mistreatment of migrant workers in the Gulf countries.

On Tuesday, about 70 former Kenyan migrant workers who worked in Saudi Arabia narrated their harrowing ordeals under their former employers, including sexual and physical abuse.

“I worked for three months without pay. When I was hospitalised, I was told that my salary had been used to cover medical bills,” Mwanamwisho Matano, a former migrant worker, said.

She said she was subjected to long hours of hard work, sometimes with little food and rest.

Matano, who travelled to Saudi Arabia in 2016, said she came face to face with racism for the first time in her life.

“The house was full of men who would call you to clean their rooms but when you get it, they would sexually harass you and assault you if you resist,” she said.

Martha Waithera said many Kenyans are forced to go abroad because of lack of unemployment, and many migrant workers lack information on the working conditions.

“Usually, what you are told in Kenya is not what you get in Saudi Arabia. It is totally different but since you have already arrived, there is little choice. You just work to get that money,” Waithera said.

She urged the government to be stricter on the recruitment agencies, saying some of them mislead migrant workers.

Waithera said proper pre-departure training is also needed, something the government has already started implementing.

She urged the government to open consular offices and safe houses in other Saudi Arabian cities to complement the Embassy in the Capital City of Riyadh.

Irungu said the government needs to ensure its bilateral labour agreement with Saudi Arabia is rights-based and includes clear protection guarantees for domestic workers.

The protections, he said, should align with international standards and address key areas such as ethical recruitment, the employer-pays principle, working and living conditions, fair payment of wages, non-discrimination, dispute resolution and access to justice.

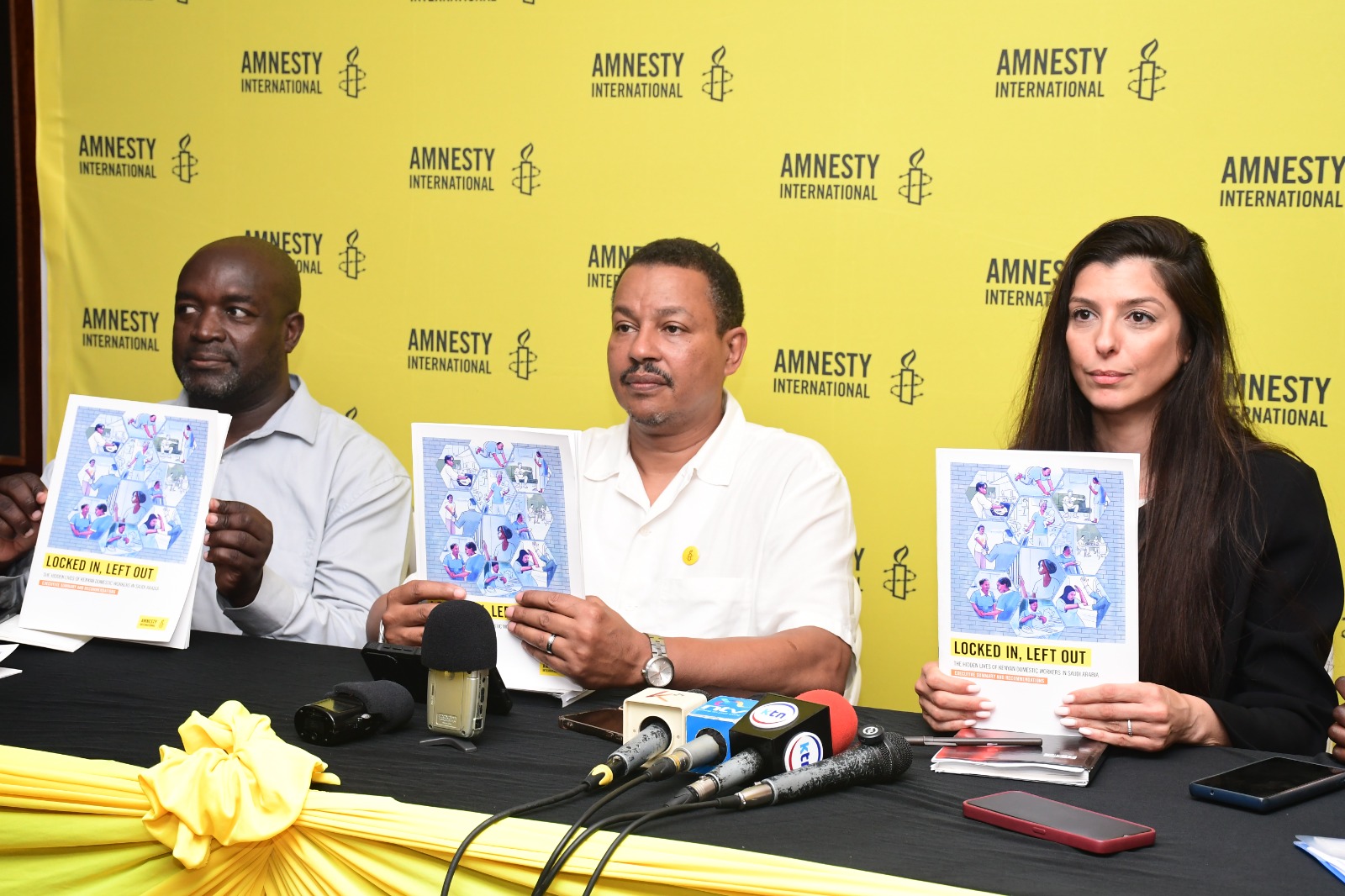

A report titled 'Locked In, Left Out: The Hidden Lives of Kenyan Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia' documents the experiences of 70 women who previously worked as domestic workers in Saudi Arabia.

“This is a significant piece of research that documents the testimonies of up to 70 women regarding the gruelling, abusive and discriminatory working conditions in Saudi Arabia,” Irungu said.

“Much of what we have described in this report can amount to forced labour and human trafficking. In many cases we have seen signs of what we would call modern slavery.”

The report documents how Kenyan migrant workers were deceived by their recruiters, made to work under brutal conditions, denied day offs, prevented from leaving the house, had their passports and phones confiscated, and went for months without pay.

Irungu said Kenya’s Labour Migration Policy needs to include a comprehensive protection framework to safeguard Kenyan working abroad.

The Saudi Arabian government should also accord migrant workers equal protection under labour laws, he said.

“Kenyans are not second-class citizens. They are similar to every other human being on the planet, and they deserve the kind of protection that Saudi workers receive under the labour law,” Irungu said.

Amnesty International Kenya wants the government to ratify the International Convention on the Rights of Migrant Workers and their Families, as well as the International Labour Organization Convention 189 on Domestic Workers, to enhance accountability.

“Furthermore, Kenya should invest more in safe houses and responsive complaint mechanisms,” he said.

Irungu said many complaints from Kenyan migrant workers in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries go unaddressed.

MPs, Irungu said, should expedite the passage of the Kenyan Migrant Workers Welfare Fund, aimed at providing financial resources for the protection and support of migrant workers.

The government has set up a toll number for Kenyans in distress to call for assistance.

Amnesty International researcher May Romanos said the experience of Kenyan women in Saudi Arabia is not unique, as it is one of the many challenges that migrant workers face around the globe.

“We want the systems to change on both sides. We want the Kenyan government to step in and support workers to migrate safely,” she said, urging Saudi Arabia to also respect workers’ rights.